J&J's Credo Versus A Mountain of Product Liability Lawsuits

- Johnson & Johnson’s vaunted code of ethics puts customers ahead of shareholders

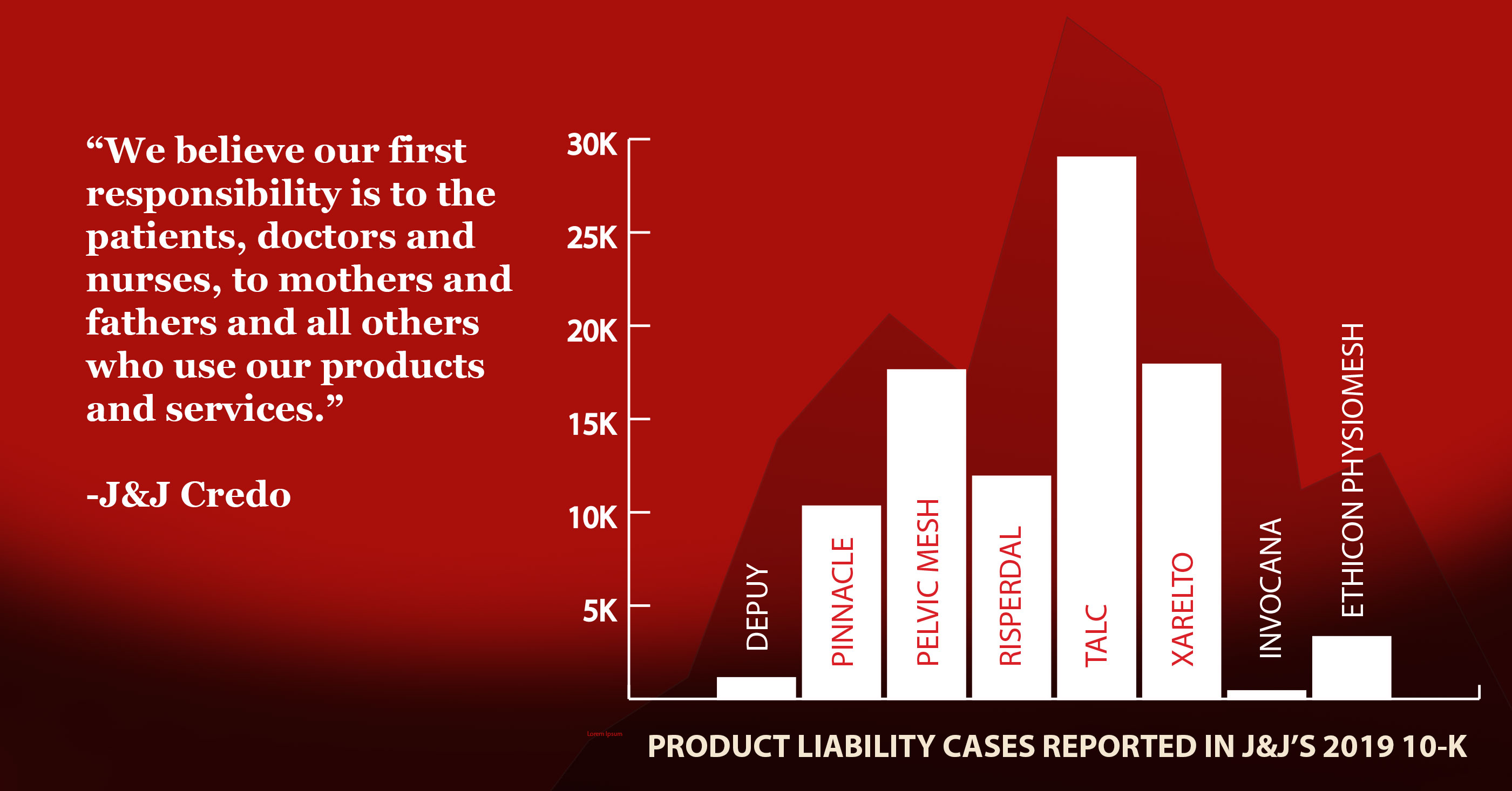

- Squaring the code with nearly 100,000 consumer lawsuits

- What J&J knew about product defects that harmed tens of thousands

Johnson & Johnson’s long reputation as a company you can trust is fueled by its famous mission statement crafted in 1943 by founding family member Robert Wood Johnson. “Our Credo” holds that the company’s No. 1 responsibility is to consumers. The credo is heavily promoted by the company internally to employees and in public advertisements. A Credo Hotline on the website enables anyone to report violations 24/7 in 23 languages. So, how does the 77-year-old code and carefully crafted image square with Johnson & Johnson’s actual performance today?

Some answers are emerging in the nearly 100,000 consumer lawsuits filed against the company over its drugs and products. Internal company documents unearthed in the course of trials shed light on what company executives knew and when they knew it.

J&J’s Role in U.S. Opioid Epidemic

Most of the attention has focused on the role of Purdue Pharma and the Sackler family in the opioid crisis which was ignited in the late 1990s by prescription drugs like the company’s OxyContin. Over-prescribing and overdose deaths quickly spiked in 1999. Today, an average of 130 Americans are dying daily from opioid overdoses, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

A public nuisance trial in 2019 in Oklahoma to hold drug companies accountable revealed Johnson & Johnson’s significant role in the opioid crisis. J&J had been the No. 1 provider in the U.S. of the active narcotic ingredient used to make opioid pills, according to findings by District Judge Thad Balkman in Norman, Oklahoma. Purdue Pharma was just one of J&J’s customers.

In 1994, Purdue was completing clinical trials of OxyContin and preparing a marketing plan to expand the pool of opioid users beyond the typical cancer patients. At the same time, J&J “anticipated demand” for its opiate ingredients. J&J began a project at company-owned poppy fields in Tasmania to create a variety of poppy that would have high levels of thebaine, a naturally occurring opiate compound in poppy plants, according to the findings.

J&J ramped up promotions of its fentanyl-based Duragesic patches and signed other drug makers to long-term opiate supply contracts.

Together, J&J, Purdue and other drug companies launched a wide-ranging marketing campaign to “influence the prescribing behavior of physicians and, thus, increase Defendants’ profits from opioids,” Balkman wrote.

“Defendants’ opioid marketing, in its multitude of forms, was false, deceptive and misleading,” the judge concluded.

Among the marketing claims cited by Balkman were that pain in general was being undertreated, patients who appeared to be addicted were actually suffering from “pseudo-addiction” due to undertreatment of pain and the need for more pills, and that the risk of addiction was low.

J&J was repeatedly warned over several years about its false and misleading campaign by both the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the company’s own hired scientific advisory board, according to the findings. Two doctors testified that the intensity of the misinformation campaign by the drug industry led them to “liberally and aggressively” write prescriptions for opioids that they would never write today.

At the end of the non-jury landmark trial, Balkman found that J&J’s “false, misleading and dangerous marketing campaigns have caused exponentially increased rates of addiction, overdose deaths” and babies exposed to opiates in the womb.

Balkman found Johnson & Johnson guilty as charged with creating a public nuisance. He ordered Johnson & Johnson to pay Oklahoma $465 million to cover one year’s worth of state expenses to clean up damages caused by the opioid epidemic. The case was the first to go to trial of more than 2,000 pending across the country against opioid drug makers.

Johnson’s Baby Powder

Johnson & Johnson’s wholesome image dates back to the company’s earliest days when, in 1894, it launched its now-iconic Johnson’s Baby Powder, followed over the decades by a line of baby products. Just whiff of a Johnson’s Baby soap or powder can trigger nostalgic feelings for the many Americans brought up on the products.

That goodwill took a hard blow in December 2018 when a judge - in scathing language - upheld a jury’s $4.7 billion verdict against J&J over claims by 22 women or their survivors that the baby powder and other talc products caused their ovarian cancer.

Judge Rex Burlison in St. Louis, Missouri wrote that “substantial evidence was adduced at trial of particularly reprehensible conduct” by Johnson & Johnson, including that the company “knew of the presence of asbestos in products that they knowingly targeted for sale to mothers and babies, knew of the damage their products caused, and misrepresented the safety of these products for decades,” according to the New York Times.

Johnson & Johnson faces nearly 17,900 lawsuits by customers who claim the baby powder or other talcum powders cause ovarian cancer or mesothelioma, a cancer of the lining of the lung caused by inhaling asbestos fibers, according to J&J’s 2019 annual report.

The few cases which have gone to trial have had mixed results. But internal company documents reveal that Johnson & Johnson has been concerned for decades about asbestos contamination of its talcum powder, according to reports by Reuters and the New York Times based on the documents.

There is no level of asbestos that is considered safe.

“Internal documents examined by Reuters show that the company's powder was sometimes tainted with carcinogenic asbestos and that J&J kept that information from regulators and the public,” Reuters wrote.

Reuters cited reports from a consulting lab in 1957 and 1958 which found asbestos in talc from the company’s Italian supplier. The Times cited memos from two different J&J executives in 1971 and 1973 raising red flags about the possibility of asbestos contamination in its talc products or at its talc mines. The Times also described instances of the company putting pressure on scientists and labs that found asbestos contamination in its talc. The trove of company documents related to J&J’s concerns about asbestos contamination is a game-changer in the litigation, providing evidence of what was previously suspected.

The $4.7 billion was one of the biggest personal injury verdicts on record, according to the Times.

Anti-psychcotic Risperdal

An even bigger verdict rocked Johnson & Johnson in October 2019 when a Pennsylvania jury awarded a single victim $8 billion damages from the company over its Risperdal drug. Although the award was reduced by a judge without comment to $6.8 million, the outrage expressed by the jury was loud and clear.

Verdicts against Johnson & Johnson over Risperdal have been on the upswing, as more information about the company’s conduct is exposed in the course of more than 13,000 lawsuits filed by boys and young men. Evidence shows that J&J created an intensive marketing campaign to persuade doctors to prescribe Risperdal to children even while the FDA had only approved the drug for use in adult schizophrenics. J&J knew from its own studies that Risperdal raised levels of the hormone Prolactin in children which made girls lactate and boys grow permanent, large female breasts.

Documents and testimony showed that J&J arranged for a medical journal article to be ghost-written and signed by doctors in academia which intentionally left out results of the company study that proved the Risperdal/prolactin connection.

By 2012, Johnson & Johnson had paid at least $1 billion to states to settle claims about its marketing of Risperdal. In 2013, J&J paid $2.2 billion to settle a criminal fraud investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice over Risperdal marketing. In 2015, a jury awarded $2.5 million to Austin Pledger of Alabama, who was prescribed Risperdal in 2002 at age seven and whose breasts grew to size 46DD. In 2016, a jury awarded plaintiff Andrew Yount of Tennessee what was then a record $70 million after hearing evidence about J&J trying to cover its tracks in regards to the prolactin test results missing from the academic article.

Trial judge Paula Patrick, in a summary of the Yount case filed in court records in June 2018, wrote that the verdict and $70 million monetary award against Johnson & Johnson were not excessive based on the evidence and Yount’s injuries. She urged the Superior Court of Pennsylvania to uphold the jury’s decision.

As of the end of 2019, there were 11,900 consumer lawsuits over Risperdal pending in courts, according to the company’s annual report.

Vaginal Mesh

Johnson & Johnson in 2005 launched and aggressively marketed a plastic mesh vaginal implant that company executives knew could fail and cause internal pain for its female customers, according to the Guardian newspaper and a consortium of European and British investigative journalists.

“Internal emails between executives, shared with the Guardian, show staff at Johnson & Johnson (J&J) were concerned that the plastic material the mesh was made from had the potential to turn ‘hard as a rock’ and roll up like a ‘folded potato chip’ inside patients… In one exchange, staff discussed how ‘shrinkage of the mesh may lead to pain,’” the newspaper reported.

Vaginal mesh was marketed as an alternative treatment to surgery to treat organ prolapse. Women around the world have complained of severe vaginal pain, inability to have sexual relations, sexual partners who have been injured by protruding bits of hard plastic, and incontinence.

More than 1,000 Australian women in November 2019 won a landmark class action lawsuit against J&J after describing their pain as “so bad she struggles to breathe,” “excruciating,” and like “there was a blade in her vagina,” the Guardian reported.

The court found J&J didn’t warn women about the “gravity of the risks” and rushed the mesh to market without adequate testing, according to Reuters. The court is still deciding how much J&J and its subsidiary Ethicon will pay to the more than 1,350 women who sued.

“The risks were known, not insignificant and on Ethicon’s own admission, serious harm could ensue if they eventuated,” the judge said in her ruling, according to Reuters.

American women had won $8 billion in settlements from J&J and other mesh manufacturers as of October 2019, according to the New York Times.

The British National Health Service found that one in 15 women with vaginal mesh needed surgery to remove it. The mesh can become embedded in internal tissue, requiring multiple procedures to try to remove it in pieces.

J&J sold vaginal mesh under the brand name Prolift for seven years until thousands of lawsuits and international investigations of vaginal mesh products by several manufacturers led J&J to pull the mesh from the market in 2012. As of the end of 2019, there were 3,300 mesh lawsuits still pending against J&J, according to the company’s annual report.

Hip Implants

Johnson & Johnson is responsible for what the British Medical Journal called “one of the biggest disasters in orthopaedic history.” In 2005, the company, through its DePuy orthopedic division, began selling a new metal-on-metal hip replacement system called the ASL-XR. The new hip made of metal balls and metal sockets was promoted as a technological advancement over plastic joints which could wear out over time. Within a few years, surgeons were finding an unusually high failure rate of the hip replacements and high levels of chromium and cobalt in patients’ blood from metal erosion. Upon surgically re-opening the patient, surgeons found a pus-like fluid and saw that muscle, bone and soft tissue had been destroyed.

Still, the company kept marketing the device.

“DePuy used a range of techniques and arguments to try to assuage fears arising from the evidence,” according to the BMJ. “…(one U.K. surgeon) was even told by a DePuy sales representative that good sources had told them that an illegal chromium ship unloaded its cargo in the river Tees a couple of years earlier and that was the reason for the raised chromium and cobalt levels he was finding in patients’ blood. DePuy declined to comment on this allegation.”

Facing thousands of lawsuits and complaints, DePuy in 2010 recalled the ASL-XR after it had been implanted in almost 100,000 people worldwide. At the same time, the company promoted its Pinnacle prosthetic as a replacement even though it had the same metal-on-metal design, according to Consumer Reports magazine.

In 2016, a federal jury in Texas jury ordered J&J to pay six patients $30 million in actual damages and $1 billion in punitive damages after finding that J&J knew the Pinnacle product was defective and failed to adequately warn the public about the risks, according to Bloomberg. A judge later reduced punitive damages by half. In 2019, J&J reached settlements totaling $1 billion to settle almost all of the outstanding lawsuits over Pinnacle hip replacements, according to the L.A. Times.

At the end of 2019, there were 11,400 hip replacement lawsuits pending against J&J, according to the company’s annual report.

Xarelto

Xarelto, developed by Bayer and marketed by Johnson & Johnson, was a new anti-coagulent drug, or blood thinner, approved in 2011 by the FDA to prevent clots that could cause deadly strokes and pulmonary emboli.

Thousands of lawsuits claimed that the public wasn’t adequately warned that Xarelto could cause uncontrolled and potentially fatal bleeding. For the first seven years, there was no antidote to stop the bleeding. The first antidote approved by the FDA in 2018 – Andexxa - cost $27,500 wholesale per patient, according to FiercePharma.

Xarelto was marketed as a replacement for warfarin, an anti-coagulant which was widely prescribed for more than 50 years. Excessive bleeding on warfarin could be stopped several ways including doses of Vitamin K.

Johnson & Johnson and Bayer agreed to settle 25,000 lawsuits over Xarelto in 2019 for $775 million. The companies did not admit liability and noted that they had won six lawsuits that went to trial, according to the New York Times.

J&J’s annual report states that there were 29,000 Xarelto lawsuits still pending at the end of 2019.